If today’s organizations have to survive and sustain themselves, they must invest in ethical capital, or they will go the way of dinosaurs. In other words, all capital ventures must be ethical, and an investment in ethics is inevitable, for it follows the spirit of Rule and an inclusive approach towards all stakeholders.

An organization wedded to value must believe in ethical leadership and develop a culture that harnesses ethical conduct, leading to the formation of ethical capital. The International Integrated Reporting Framework must work towards including ethical capital as a distinct capital.

A good organization depends on its ethical status for its success. Tata Group of companies in India is one example of a conglomerate that thrives on its ethical positioning. LIC of India, with its excellent market communication and tagline – Zindagi ke saath bhi- Zindagi ke baad bhi,( जिंदगी के साथ भी, जिंदगी के बाद भी) has leveraged its ethical status to emerge as a deep brand- an example of ethical capital. LIC of India, no wonder, is also considered a trusted brand for its fair and ethical customer dealings.

‘Ethical capital is a transformative force in reimagining economic systems for a sustainable and equitable future. Rooted in the relational framework of field economics, it underscores the interconnectedness of human and non-human actors within dynamic networks. By fostering trust, reducing systemic inefficiencies, and aligning economic activities with collective well-being, ethical capital challenges entrenched paradigms of profit-driven, individualistic value creation’. ( Prabhakaran 2025)

‘Ethical capital is the collective value that derives from the organization’s commitment to ethics’ ( Cynt Schoeman -2019). It necessarily means that the value of ethics should be ingrained in all the six capital models, i.e., financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capital. The degree of impact value may vary depending on the capital source. The degree of impact on the human capital that fosters people’s competencies, capabilities, and experience is very high as it is key to implementing an organization’s governance outline, strategizing risk management approach, and stimulating ethical values in keeping with the overall shared value of the organization. The degree of value of ethics is reasonably high in social and relationship capital as it strives to build trust and willingness to engage with stakeholders and creates value that complements other sources of capital; however, the same intensity is not found in other sources of capital. Ethical capital must be the core value-creation strategy of all surviving and flourishing organizations. The context of ethical and individual capital differs – the former encompasses the broader communal approach , the latter is individual in approach. While human capital primarily focuses on individual economic returns, ethical capital operates within broader communal contexts where transparency, trust, and fairness are prime considerations, making it a collaborative process. Ethical capital encompasses skills, knowledge, cultural or social assets and works for the collective well-being of economic systems (Prabakaran, 2017).

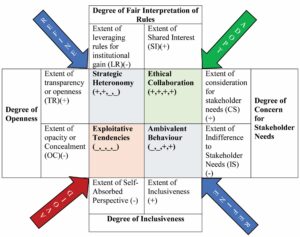

Here is a model (designed by erudite academician –Prof Madhu Prabhakaran) that will help understand an insurance business’s assessment of ethical performance (capital). Ethics in this model has been shown as the sum total of four deciding and dynamic factors: degree of fair interpretation of rules, degree of openness, degree of inclusiveness and degree of concern for shareholder needs. A business can take four positions within these broad guidelines. It can position itself with strategic heteronomy, exploitative tendencies, ambivalent behaviour and ethical collaboration. Ethical responses are better gauged vis-a-vis their business relation with stakeholders, shareholders, consumers, vendors, employees, ecology and, of course, the regulatory authorities. Being Ethical is a process and, therefore, dynamic–moving from one extreme (autonomy) to another (heteronomy); transparency to opacity, care to apathy and cosmisus (inclusiveness) to narcissus (self-absorbed perspective). A business’s positioning regarding the above deciding and contrasting factors determines its ethical capital.

Let me discuss each quadrant. The first quadrant falls in the category of ‘Strategic Heteronomy’. It has two plus and two minuses. The degree of fair representation of rules suffers here as rules are leveraged for institutional gain (LR s.) The business tends to become unethical when it makes decisions guarding its self-interest. In its decision-making, it is perceived as fair as most of its decisions are transparent and care about its different stakeholders, particularly its customers, somewhat reasonably. The business tries to reach out to them with wider choices. Still, the degree of narcissism (self–obsession) tends to be very high. The business becomes an attention seeker and wants to be admired; as a result, it tends to ignore the feelings of others. The result is that despite good intentions and a fair amount of transparency and care for shareholders, most customers perceive the business as more inclined towards protecting its interests. For example, in health insurance, most companies come out with exhaustive coverages – detailing and explaining well the coverages, but they are so self-obsessed with their products that they forget the customer’s genuine wants – as a result, lots of cosmetic covers are offered to them without trying to understand their actual wants. It also protects itself by putting a copay in each such offer, much to the chagrin of the customers. It is enamored with its product so much that it tends to overlook the actual wants of customers and cleverly guards its ostensible offering as well. Today’s market is flooded with flashy offerings that often go as innovative products. A business in this position needs to refine some of its decisions. It must come out of the self-obsession shell and work for shared gains. It is understandably tricky as a business has to work for institutional gains.

The second quadrant is ‘Ethical collaboration’ – It has all its pluses. The business believes in shared interest and shows high consideration towards stakeholders; as a result, all its actions and decisions are tuned towards this objective. The actions and activities of the business are highly holistic (cosmisus). The business is open and caring towards all in its endeavours. It allows an autonomous organization to make decisions that appeal to all and are fair, transparent, and inclusive simultaneously. In India, LIC uses ethical collaboration to build a deep brand, leveraging ethical capital to the hilt. Its popular policies are transparent and inclusive. It handles death and maturity claims well on time. It is perceived as a trusted partner by most customers. While securing protection during the policy period, the policies gave reasonable returns on maturity. The fact that it continues to be the market leader despite enormous competition is a testimony to its ethical collaboration and leadership with all shareholders, particularly the customers.

Our assumptions about ‘homo oeconomicus’, or economic human, were somewhat hazy. We presume that they could make rational decisions. However, the model fails to read people’s actual behavioural patterns. It may be noted here that understanding and predicting insurance purchasing decisions is a complex decision-making process rooted in behavioural science. Most customers’ decisions depend on how the various choices are presented to them. The appealing and meaningful way choices are significantly framed matters to the consumers. If a pension product is presented as if it would guarantee the same level or desired level of lifestyle as before, it possibly would be perceived as more inclusive. In that case, it would be explained through sheer consumption rather than pure investment. The trade-off between consumption and investment needs to be better explained and explored. As a pure investment product, life insurance faces many competitors. A mutual fund is a better investment option. Still, it cannot provide the protection and safety valve life insurance offers as such life insurance products should highlight the consumption aspect alongside investment to stay afloat in the market. In such a scenario, an insurer will be very caring and aware of the consumer’s life cycle needs. While delivering, the insurer is transparent and inclusive as it covers the varied needs of your customers. If ‘framing’ (Geneva Report) is taken care of at the product design level, then the components of care, shared interests, and holistic, inclusive approach manifest in all such product presentations. The choice is with the organization to use autonomy to delve deeply into the psyche of insurance purchasers and understand their life cycle needs. As an insurer, it can’t afford to be transactional. It has to build a perennial relationship with customers by developing products that suit their changing lifestyles and lifecycle needs.

Ethical organizations always try to adopt this position and refine their decisions to maintain this ideal position.

The third quadrant is identified as ‘Exploitative Tendencies’, with all minuses. The business relies on brute force rather than the Rule of Law. It uses its unlimited power over other people, often unfairly and cruelly. I will explain this positioning that an insurance business takes with an example of health insurance for senior citizens. Senior citizens pay a very high premium for even a reasonable cover of 5 to 10 lakh (reasonable in today’s context). They keep paying premium religiously every year despite their shrinking income. Suddenly, during a policy renewal, they are told they will have to pay an increased premium as high as ten thousand or even more without citing any reason. Many of them have not taken a claim in the last five years as they predominantly suffer from chronic diseases for which hospitalization often is not required. It may be noted here that a health insurance policy is triggered only in case of hospitalization. Health policies hardly trigger for other kinds of institutional settings, far better suited to senior citizens. On enquiry, they are sometimes informed that one of them or both has migrated to a higher age bracket –the reason for seeking the higher premium. The rise of premium is based solely on the advancement of age, and no consideration is given to maintaining good health or healthy behaviour. There is so much hype on technology, but even the new-age insurance companies have been unable to shed their deeply ingrained legacy underwriting practices. Is it not a travesty that a person maintaining good health, not preferring claims for years, is punished in this manner? Senior citizens’ health insurance products are often designed with a copay of as high as 50%. Over and above, even legitimate claims are not paid on flimsy grounds. A TPA would usually disallow an expense allowed by the hospital on the score that the expense is not medically necessary. The poor customer has to bear those expenses unwillingly. The insurance company is highly narcissistic in its approach – It provides senior citizens ostensibly with a health insurance product; however, that comes at a very high cost. They protect their claim outgo with steep copays and interpret the opaque policy wordings to their advantage. The business in this quadrant gets mired in exploitive tendencies. Every business should avoid this positioning.

The fourth quadrant is identified as ‘Ambivalent Behaviour’ marked by two pluses, i.e., the degree of applying rules for shared interest and holistic or inclusive approach. Still, it gets affected by two minuses, i.e., degree of opaqueness and degree of apathy. The business believes in shared interest and is accommodating but falsely preys on opacity and a degree of indifference or apathy to shareholders. A person buys motor insurance and a health insurance policy from the same company. To their utter surprise, they find the treatment of misrepresentation is very different in both policies. In health policy – even on an innocuous misrepresentation, the policy can be voided by the insurer.

On the other hand, in case of misrepresentation, in motor policy, – he may be paid the claim even if the payment gets compromised, but the policy is not voided. The different treatment makes an insurer’s offerings very opaque – an ordinary insured finds it challenging to comprehend the differences in both policies. This makes the insurer’s position ambivalent, with two sets of different interpretations for similar policy wordings. The huge misselling in the insurance market results from apathy or sheer inertia on the part of the business (insurance) to address this imbroglio. The bancassurance model is a massive disappointment, with banks indulging in misselling very high. A poor account holder who prefers a health insurance policy through a bank often does not get to know the coverage adequately. It results in huge disappointment when she chooses to claim. She finds many things are either not covered or not paid adequately. Despite the shared interest and inclusive approach, the business tends to lapse into unethical practices due to non-transparent and somewhat casual approaches to business. The business needs to refine or rediscover its decision to escape the ambivalence.

Therefore, ethical capital is a conscious decision a business needs to take to emerge as a winner in the marketplace. The Adopt, Avoid, Refine Investment model in Ethical Capital needs to be translated into actionable strategies by adopting ethical practices, forging ethical collaboration, avoiding exploitative tendencies, and refining inconsistent behaviors.

Model developed by Prof( Dr.) Madhu Prabhakaran (2025)

By: Prof.(Dr) Abhijit K. Chattoraj – Chartered Insurer, Insurance and Risk Management Professor and Director of Management Development Program & Consulting -IMS Unison University, Dehradun.